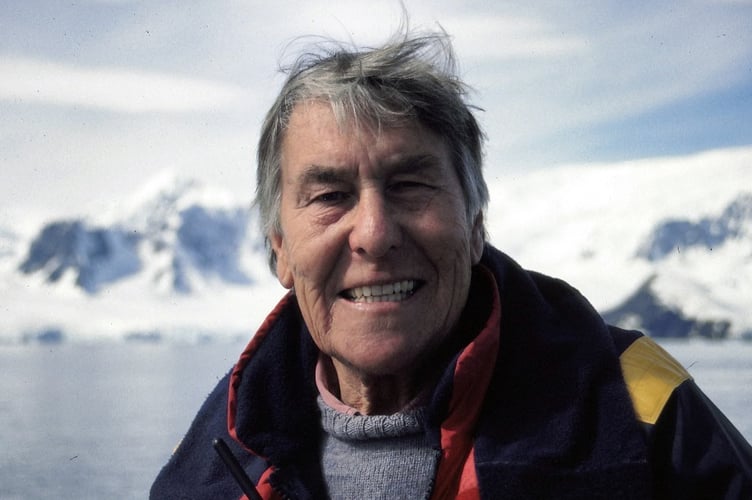

Tony Soper, our special Devon naturalist, TV personality and leader of wildlife cruises, died peacefully on 18th September. The next day there were appreciations of him, in the Times, the Telegraph and the Guardian and on both national and local television.

Tony was born in 1929. His father managed Cattedown Wharf and Tony spent hours there as a boy, loving the atmosphere of the harbour and watching the wildlife go by. He passed for Devonport High School for boys and worked his way up to the sixth form but he did not want to go away to college. He wanted to enter the world of broadcasting and as soon as he had left school in 1947 he went down to the BBC in Seymour Road and asked for a job. He was persistent and soon they took him on as a trainee, with courses in London as well as at home in the south-west.

He decided to concentrate on studio production and in 1950 was posted to the Bristol studios. His managers were Desmond Hawkins and ex war- correspondent Frank Gillard. He got on very well with them, for he worked hard, with enthusiasm and for long hours. In Tony’s words, “I made myself indispensable.” He was willing to have a go at anything. From a base of radio, they began to develop nature programmes for television. He knew several people who had made films on nature topics; there was H.G.Hurrell, who lived on Dartmoor and had come to talk to the boys at Devonport High School, and Gerald Durrell, who had been collecting animals for zoos and housed them for some time at Paignton Zoo. These films, in programmes produced by Desmond Hawkins and Tony, were very successful.

Tony approached Desmond Hawkins and suggested they set up a unit to start making their own nature films. Hawkins thought this was a great idea and they walked down into Bristol high street together and bought a cheap Bolex movie camera. The BBC Natural History Unit was born that day.

Tony made contact with many of the foremost naturalists. His friendship with Ronald Lockley, who had rented and farmed the island of Skokholm, in Pembrokeshire, was to last a lifetime. It started with Tony volunteering to help mark seal pups from grey seal colonies round the Pembrokeshire coast, with messy tar. They used a canvas curragh to row and sail along the coast. They both also studied the thousands of puffins that nested on Skokholm and Skomer.

In 1955 Desmond Hawkins and Tony went to a lecture given by Peter Scott, the son of Scott of the Antarctic and founder of The Wildfowl Trust at Slimbridge. They developed the idea of a regular nature programme with Peter Scott presenting and Desmond Hawkins and Tony producing. They called it ‘Look’ and it ran from 1955 until 1969. Tony was to remain a good friend of Peter Scott and one of the hides at The Wildfowl Trust at Slimbridge, is named after Tony.

Tony soon progressed from the Bolex camera. He took a waterproof model to film Atlanta, H.G.Hurrell’s rescued seal. The Hurrells kept Atlanta in their outdoor swimming pool, and Tony and Altlanta swum together as he filmed. He also swam with Peter Scott, who grew to love diving with the colourful fish in tropical waters. On one occasion he was both filming and keeping an eye on Peter Scott, for safety reasons, as it was an area where sharks patrolled. Tony had been distracted and looked up to realise there was no sign of Peter Scott. He had visions of the headlines – ‘Famous naturalist killed by shark!’

He remained busy filming and producing nature programmes for the BBC but he was very versatile. Many remember his part in ‘Animal Magic’ with Johnny Morris during the ’60s. They were good friends; Tony exchanged his motorbike for Johnny’s van. In 1965 Tony wrote his most successful book, ‘The Bird Table Book’. It was a best-seller for over forty years. Soon after this, in 1967, he began the annual winter cruises, up the River Tamar from Plymouth to see the wintering avocets and many other birds. People would go year after year and the cruises continued for over twenty-five years. For about three years in the late 1960s Rowena Cade asked if he could manage the organizational affairs of her wonderful cliff-side drama project at the Minnack Theatre. He loved it.

At about this time he married Hilary and they settled at Dartmouth, where he wrote ‘Wildlife of the Dart Estuary’ and later moved to Gerston Point by the Kingsbridge Estuary, where they brought up their two children, Tim and Jack in idyllic surroundings.

Now as a freelance, he continued making programmes with the BBC, with series including ‘Nature’ and ‘Go Birding.’ In the studios at Plymouth he made many short programmes, one of which included a group of primary school children from Modbury examining sea-shore creatures with him – he was so good at calming the children’s nerves and making them laugh. He wrote many books; especially successful were ‘Penguins’ and ‘Owls’ that he wrote with John Sparks. Of all his books, the favourite for Barbara and me was ‘Oceans of Birds,’ which takes us for a cruise around the world. Part of this cruise he shared with Hilary and their sons, Tim then about 12 and Jack about 8. It has been one of the most important educational experiences in their lives.

It was during the ’80s that going cruising really took off for Tony and through the ‘90s began a love affair with the Arctic and Antarctic that continued until he was well into his eighties. He reckoned he had crossed Drake Passage, off the tip of South America, at least a hundred times. He always put the satisfaction of those on his cruises as his top priority. Once on an Antarctic trip, the Zodiac boat on which he was perched, came crashing down on the deck. His leg was very badly broken. The captain immediately went to change course for the nearest hospital, in the Falkland Islands. Tony wouldn’t hear of it. He was determined that his ship-mates would see the king penguin colony and so spent several extra days in great pain. Luckily, the Queen’s orthopaedic surgeon was visiting the Falklands hospital and did a first-class repair job.

Tony shared his knowledge of these cold but fascinating places in books on the wildlife of the Arctic and Antarctic and on the North-west and North-east passages which are all still available.

When Bryan Ashby and I were taking one of our Family Naturalists’ courses at Slapton Field Centre, Tony came to give us a slide show about his cruises in Antarctica; he had the children’s complete attention. Although they enjoyed the penguins, the icebergs, and the ill-mannered elephant seals, the thing they will always remember is singing with Tony that little-known sea-shanty for those suffering sea-sickness:

“My breakfast lies under the ocean, My luncheon lies under the sea,

And if we continue this motion, Oh, what will become of my tea?”

Tony was very modest, never wanted any fuss and never pushed himself forward. He was a wonderful communicator, with a fund of knowledge and fun. He made friends with people of all sorts, from all over the world. We, who live in Devon, can be proud of him.